It is a mistake to stop at the surface violence on the streets. Kashmiris of every inclination are longing for moderation. And most of all, reprieve, says Shoma Chaudhury. With Zahid Rafiq

|

Ready for more A stone-pelter prepares for another day’s battle in Srinagar

PHOTO: ABID BHATT |

|

IT IS tempting to think of Kashmir as an old story you know everything about. For 20 years, it’s been one of the most reported conflict zones in the world. In a sense, everything about it has been said. But familiarity is not necessarily the same thing as understanding. Or empathy. No coverage you see on your television screen, for instance, can prepare you for the devastating landscape of lived pain in the Valley. It cuts through all the conspiracies. It quivers everywhere beneath the skin. It spills out of every stranger you meet. It flows beneath everything that happens. How Fancy Jan was shot dead by the security forces, just drawing the curtains in her room before her marriage. How Umar was five the first time he felt the cold nozzle of an army gun at his neck. How Tamim was getting a haircut before Eid, when drunken troops barged into the saloon and he thought he was going to die. How 10-year-old Shafiya, searching for her brother in school, got caught in army and militant crossfire and watched a 80-year-old man fall head first into a drain when a bullet whizzing past her hit him instead. For most of us, Kashmir is nothing more than an opaque geo-political riddle in a far away corner of the country. But for those who live there, just one afternoon’s conversation with one ordinary family in downtown Srinagar can straddle all these accounts of fear and untimely death. Imagine what the Valley’s collective memory holds. Wounded is an inner state of being in Kashmir.

OVER THE past four months of enraged stone-pelting then, Kashmir has again been trying to tell India a profoundly complex story. Words have failed the Valley before. So have guns. Now even its stones are starting to get hoarse. It’s suicidal to still not be listening.

Yet, if you go by the average talk in India, the dominant mood towards Kashmir is fatigue, bewilderment and prejudice. What do Kashmiris want? most Indians ask. What does “azadi” mean? What’s this “political solution” they go on about? India is pumping so much money into Kashmir, why are they still so ungrateful? Why are they so communal?

Over these past months, in fact, as thousands of young boys have hurled themselves bare-bodied at security forces, pelting stones with a kind of unprecedented fury, India has contented itself with merely asking the surface question: Who is behind this? Who is orchestrating it? Not even the sight of young boys willfully daring death, unarmed — boys born in the shadow of militancy and aware of the might of the gun — has evoked enough curiosity to ask: Why are they doing this? What’s driving them? What’s changed? (As a young stone-pelter says with angry frustration, “Why can’t you understand, we are not just a piece of land, a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan. We are human beings with emotions.”)

It took 110 dead boys for India to send a high-profile all-party delegation to the Valley. Still, Kashmiris counted it as a soothing gesture. Suddenly the stone-pelting stopped: Perhaps too many boys had already been arrested (the official police estimate is 2,219); perhaps the immediate upsurge had exhausted its shelf-life; perhaps the pelters’ “handlers” were persuaded to call for a temporary break. Or perhaps, people’s expectations just went up: What would India concede?

Unfortunately, India has done very little. First the Centre came up with a disappointing eight-point formula yielding nothing but cosmetics. Then it announced its interlocutors — journalist Dileep Padgaonkar, academic Radha Kumar and bureaucrat MM Ansari: eminent but toothless. Where Kashmiris had been waiting for a breakthrough idea — a multi-party parliamentary Standing Committee on Kashmir led by seasoned politicians like Pranab Mukherjee, Digvijay Singh, Arun Jaitley and Sitaram Yechury — it got a little more of the same old, same old. Track two well-wishers with no political clout.

Sitting in Delhi, it is difficult to imagine the despair these decisions must send through the Valley. Kashmir is hostage to many cankerous dualities: Power struggles between India and Pakistan; power struggles between the Centre and the state; power struggles between the National Conference and the People’s Democratic Party (PDP); the moderate separatists and hardliners; the army and the police; the myriad intelligence agencies. Pigeon-holed between all of this, Kashmir might seem like an old intractable story no one really wants to tackle. But, ironically, that’s exactly what the desperate stones being hurled at India are saying: Life here is unbearable. Why aren’t you listening to us? Why aren’t you doing something?

It is the most direct one-way conversation Kashmiris have had with the Indian State in decades. With the bruising years of militancy now several years behind it, it’s as if a whole new generation in Kashmir is poised on a psychological tipping point. It could go either way. But the key thing is, beneath the apparent violence and arson of the last few months, new things are brewing: A new mood, a new generation, a new window of opportunity. But as a Valley journalist puts it, “India needs to stop taking our temperature now and start treating us.”

Aurally, the visceral cry for azadi rising out of Kashmir might seem like a daunting and non-negotiable dream. How can Kashmir survive as an independent nation with China, Pakistan, India, Afghanistan and the US all foraging in it? But azadi means many different things to different Kashmiris — ranging from complete independence to porous borders to new trade routes to autonomy to a pre-1953 position to, at least, a primary freedom from the security apparatus that overwhelms every aspect of a Kashmiri’s daily life. Beneath all of that, the great discovery of visiting the Valley after the surface violence has abated is that ordinary people of every inclination are longing for moderation, dialogue and resolution. And most of all, reprieve.

A few weeks ago, Congress president Sonia Gandhi said, “We must ask ourselves why people in Kashmir are so angry and hurt.” Union Home Secretary Gopal Pillai also said, “There is no doubt India has made many mistakes in Kashmir. We have spent a lot of money in the Valley but not been able to win the hearts and minds of the people. We have to ask ourselves why.”

The answers are literally being hurled back. It will be tragic if India remains deaf to this moment. Or mistakes the lulls for “normalcy”.

|

Praying for peace Women on a roof listen to hardline Hurriyat leader Geelani

PHOTO: SHOME BASU |

|

THE PECULIAR opportunity and neurosis of this moment in Kashmir lies in the nature of the stone-pelters. More than the separatist leaders — Syed Ali Shah Geelani, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and Yasin Malik — who have traditionally voiced dissent in the Valley, it is these young boys who now hold the key.

If you were to go by intelligence inputs, you would dismiss them as mere “miscreants”, as Chief Minister Omar Abdullah did in the beginning. Disaffected, unemployed youth rented for a few rupees to create trouble. If you went by police inputs, the appraisal would be roughly the same. “Fifty percent of them are students and you know how easy it is to brainwash young minds,” says Shiv Sahai, IG, Kashmir Police. “The remaining 50 percent are drug addicts and out-of-work shikhara walas, vendors and small shopkeepers.” The underlying assumption is that the boys are being orchestrated and have no political agency of their own.

There may be a small grain of truth in this. There are signs that underground leader Masarat Alam, the general secretary of the hardline Geelani-led Hurriyat faction, is a big inspiration for the pelters. But he is by no means the sole architect of the campaign. In 2008, after the Amarnath land row, he had come up with the hugely popular “ragda” campaign, which involved a furious rhythmic stamping of feet to scathing slogans about India. This time round, he has coined the ‘Go India Go Back’ slogan, and has been urging pelters to consolidate opinion on the Internet. Alam is about half of Geelani’s age, who is 83; he has the pulse of the new generation, and the talk in Srinagar is that at least part of this upsurge has been a flexing of muscles in the succession battle heating up for the aging Geelani’s position.

(Several thought leaders in Srinagar, in fact, are worried that Delhi is playing dangerously with the “Bhindranwale card” again: Allowing a hardline leader to grow in stature to serve its own labyrinthine purposes. Alam, incidentally, was released from jail just a few days before the stone pelting swelled to a crescendo.)

Yet none of this seems the whole truth. Alam, who has been endorsing the stone pelting while other leaders have remained silent or ambiguous, seems to merely be riding a popularity wave. The pelters themselves have swirled out of the range of any specific leadership. To Delhi, it looks as if Geelani has emerged as the undisputed guardian of the ‘Kashmiri sentiment’ — the timekeeper of its anger, the high priest of its hartal calendars and school lockdowns. But both Geelani and the boys know that he is merely reflecting the mood on the street. Significantly, Geelani is a known votary of Pakistan, but this year when he tried to mark 14 August as Independence Day, the pelters refused to comply. They even burnt Pakistan-based United Jihad Council commander Syed Salahuddin’s effigy for suggesting that the hartals should be called off.

After the surface violence abates, you realise people of every inclination are longing for moderation, dialogue and resolution. And most of all, reprieve

|

|

IT IS clear these boys are different from the generation that crossed the border in the 1990s to trigger the militancy. They have been born out of conflict and have seen its ravages: This makes them both angry and aspirational. They are viscerally anti- India but also anti-Pakistan. They are speaking a dogged new language of non-violence but are not above picking up the gun. They threaten to engulf India in a new round of bloody militancy but keep cajoling it not to push them that far. They have a disarming collegiate politeness but are floating on a lethal helium of rage. Their talk has an undertow of radicalised Islamic rhetoric, but they are proud of Kashmir’s syncretic traditions. They are uncomfortable with being typecast.

“We have grown up in the debris of a burnt house. At least the earlier generation knows what they want to go back to. We only know the burnt house,” says one young journalist and pelter sympathiser. “We are the fire and India is throwing petrol on us,” says another, vividly illustrating how they perceive the Indian security forces’ shoot orders.

In a sense, Rafiq (names changed) epitomises this new generation. He is one of downtown Srinagar’s most committed stone-pelters. He’s about 23 and a BCom graduate. His father is a government servant who has already paid Rs. 60,000 to the police as a bribe to keep Rafiq out of jail. But Rafiq persists behind his back. He’s one of the front-line boys — “We assess each others’ gurda (guts) and decide who’ll be in front,” he says. We are sitting with Rafiq’s younger brother Muzamil and friend Nawaz at the edge of Pari Mahal, a beautiful hilltop garden in Srinagar. The boys have the easy, fidgety energy of the young. There is nothing to connect them with the dark pictures Rafiq is showing on his mobile. Pictures of himself swaddled in a mask hurling stones at Indian security forces. Pictures of friends shot at close range through the neck and abdomen. Pictures of seething mobs carrying away bodies. The disjunctions are surreal.

Rafiq says he’s written a poem and pinned it on his cupboard. “I don’t want my teenage going,” it says, “give me some stones/ if I die in the battle zone / box me up, pack me home / put my medals on my chest / tell my mom I did my best / tell my love not to cry / I am a young Muslim born to die.” The naivete is almost teary. The boys have also cut themselves an anthem online. “We have no army, we have no land, we only have the stones in our hand,” goes the song. When you task yourself to step out every day, unarmed, to face security forces geared with tear gas shells, pellet guns, and lethal weapons you take what motivation you can get.

|

Unequal battle More than 2,200 boys have been arrested during the recent crackdown

PHOTO: ZULFQAR KHAN |

|

It’s been difficult to bring the boys up to Pari Mahal. They are all on the run from the police. They meet us furtively in downtown Nawa Kadal, looking frequently over their shoulders for informers or cops. As the car pulls away, Rafiq begins to talk. At almost every turn, he points to a milestone: This is where my friend Shaheed Muntazar was shot in the stomach. This is where a bus conductor, Tango Charlie was shot. He had three kids. He wasn’t a friend but I had shared a cigarette with him just before he was shot. Other names trip off his tongue. Sameer, the 8-year old boy shot in Batamaloo; Abrar 18, shot in the chest. Thufayil Mattoo shot playing cricket. Abid, shot in January this year. Hasan Pacha shot in 2008. A boy they call Mandela, who’s been shot twice, once in the heart, once in the leg, but who’s survived and is still pelting.

Rafiq is 23, but all his talk is of the untimely dead. It slides off him with unnerving ease. You wonder what such proximity to death has done to the boys. Then he talks of an episode that turned him into a lead stone-pelter. “We were protesting the economic blockade when they shot a boy straight in front of me. His brains came out. I just went mad. I leapt on the police jeep with bare hands. The man standing on top fired on me six times. Somehow, he missed me. From that day, I’ve been pelting stones.

WE HAVE three very clear reasons why we are on the streets,” he continues. “We are protesting the atrocities by security forces. We are asking for the right to self-determination. And we are asking for azadi. No one is orchestrating us. We have lots of stones here; we don’t need Pakistan’s help. This time we haven’t started with the gun, ma’am. We are a non-violent, peaceloving people. Everything is now in India’s hands. This time do something, show something for Kashmir. Please, please, please ma’am. If we are burning buildings, there is some reason for it. We are not being used by any leader. When we are on street, they are on stage. But if they don’t reflect our views, we’ll cast them aside.”

The “please, please, please ma’am” echoes incongruently. Just as we’re leaving, I ask him what lies ahead for him. He’s applied for a MBA course in Delhi, he replies sheepishly. The collision of anger and aspiration. What will happen to his revolution, I ask. I’ve reached my retirement age, he laughs. There are many kids behind me.

Fifty kilometres away in Anantnag, a similar tableau plays itself out: the broken, heart-constricting stories of death; the attendant anger and despair. We are at young Intiyaz’s home. He was shot dead on June 29; he was 15. His father is a taxi driver. They had just saved enough to start building a house. It was a big event. The workers were on food wages because they could not afford more. We ask the parents what they most remember about their son. It is a terrible moment. Something akin to an electric shock goes through them. “He loved cricket,” the father says, and both his wife and he crumble, rasping for air. Apparently, Intiyaz never used to do any work. On that fateful day, his father asked him to drop his cricket and sent him to buy bread for the labourers. There was some stonepelting on the main road. The CRPF chased Intiyaz, along with the mob, a kilometre and a half off the road, back in front of his house and shot him in full view. “They could have burnt my house down,” the mother cries repeatedly, “why kill my son, why kill my son.” The sister says in the kitchen stoically. “We want azadi.”

The stone pelters are viscerally anti-India but also anti-Pakistan. They are speaking a new language of non-violence but are not above picking up the gun

|

|

Later, in the same neighbourhood, a group of stone-pelters don masks and allow us to interview them on video. Fascinatingly, the same reiterations flow: the dogged insistence on non-violence, the protest against zulm (injustice); the dismissal about any particular leader as central to their movement and the plea to India to do something this time.

Here, even more than with the boys in Pari Mahal, one can feel a palpable despair. “We are not against Indians, ma’am,” says one boy. “We are not even against the CRPF — they are also human. So many boys have been killed, has a single jawan been killed? We just want them removed from our lives. We want azadi.”

|  |

Scarred lives Broken windows and shattered dreams are a common sight all over the Valley

PHOTO : KAVI BHANSALI | Collateral damage A protester in Srinagar shows injuries on his back caused by pellets

|

|

Kashmir is like a hall of mirrors where for every image, its reverse reflection is also true. But when you talk directly to these boys, it’s easy to forget the cynical theories floating around about them.

ZULM IS a big corrosive phenomenon in Kashmir. It looms over everything like a giant cat’s paw over a country of mice. Even more than azadi from India, people in Kashmir first unanimously want azadi from the security forces. For the boys certainly, it seems the primary goal.

But it’s not just the boys on the street. Alienation courses through every strata of society. “How can we feel a part of India,” says a systems assistant in a hotel, who has studied in Bengaluru. “We live here. This is our home. We are educated, we have college degrees. But we can still be stopped by a CRPF jawan from Bihar who may be just a Class VI pass and we have to explain where we are going and who we are. It should be the reverse. We should be asking others where they are from, and what they are doing here. There are no jobs here, but I still want azadi.”

“Kashmiri Muslims feel powerless and marginalised,” says Mohammad Gul Wani, a political science professor at Kashmir University. “The feeling of being a minority is not merely a numbers game.”

It’s true. Alienation in Kashmir arises from a variety of things: daily frisking, humiliations, fear, curfews, hartals, abusive encounters, random arrests. Almost every window pane in Kashmir is smashed. Almost a decade after militancy was crushed, the security prism through which the government looks at Kashmir has not shifted. Democratic dissent is the demon now. Rallies and demonstrations are never allowed. The local cable television network has been forcibly shut down, the human rights course in Kashmir University has been withdrawn, research papers on contemporary Kashmiri politics are disallowed.

Even doctors are not immune. In a small anteroom in one of Srinagar’s major hospitals, two doctors show pictures of stone-pelters shot in the neck and chest. There is a CT scan of a skull sprayed by a pellet gun. It is a daunting sight. Pellet guns were meant to stun animals during hunts, but it was too painful and was disallowed. Now the same gun is being used on the pelters. “Most of these have been targeted killings,” says one doctor, but he’s too afraid to put his name on record. There are plainclothes policemen everywhere in the hospital; sometimes the forces come into the operating theatre; once they threw a tear gas shell into the hospital lobby. The doctor talks of how he had turned a militant- patient away once, too scared to treat him for fear of repercussions. “A doctor is supposed to treat anybody. I have never told anyone about it before,” he says, “but that episode made me ashamed of myself. That is what this place does to you.”

By the security agencies own admission, there are only about 250-500 militants left in Kashmir. During the PDP-Congress government, some of these confidence building measures had begun: POTA was revoked, CRPF bunkers began to be withdrawn from civilian areas, the army was asked to monitor only the borders. Still, it would be a colossal mistake to imagine that merely minimising the security apparatus in civilian life can substitute for the “political solution” Kashmir seeks.

|  |

A day in the life... The young generation (far right) has been born out of the Kashmiri conflict and seen its ravages

PHOTO : SHOME BASU, ABID BHATT |

|

LIKE THE enveloping feeling of zulm, a sense of unfinished history stalks almost everybody in Kashmir. Even a vendor on the footpath will take you back to 1947 and say, “Nehru ne bola tha ki aam aadmi ka vote lenge…. (Nehru had promised a plebiscite to determine whether Kashmir should accede to India or Pakistan).”

With its internal implosions, in many ways, unlike the tumultuous 80s and 90s, merging with Pakistan no longer seems a dominant object of desire in Kashmir, but the community still wants a restoration of essential dignity: it wants to discuss the terms of its identity as a conversation between equals conducted under due process. “If Dr Manmohan Singh would just make a statement acknowledging that a section of Kashmiri people have a grievance and these are the reasons his government can’t give in to those demands, but he would be happy to talk about it, half the battle would be won,” says People’s Conference leader Sajjad Lone.

Unfortunately, neither the Centre nor successive state governments in Kashmir have been sensitive to this. After the tribal invasion and Maharaja Hari Singh’s hasty letter of accession to India in return for Indian army help, the Centre has continuously eroded Kashmir’s autonomy under Article 370. With Sheikh Abdullah jailed, and a pliant government under Chief Minister Ghulam Mohammad Bakshi in power, the Centre revoked many of the clauses that had protected the Kashmiri idea of self, including two that allowed Kashmir’s political head to be called a Prime Minister and the governor to be elected by the Assembly. A murky history of rigged elections and substitute governments followed. As a top police officer says, “Kashmir’s real tragedy has been the denial of democracy. If the Centre would stop setting up puppet state governments, things would improve automatically.” And as Lone says, “India forgets it does not have to give us autonomy, it has to restore it.”

But to untangle these vexed questions of history, one needs inspired leadership at both ends. Kashmiris still remember former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee with admiration and gratitude for coming to Srinagar and offering a hand of friendship to Pakistan, saying India was willing to discuss the Kashmir problem “insaniyat ke dayare mein” — within the “boundaries of humanity.” Former Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf’s offer to look for “out-of-the-box solutions” and Manmohan Singh’s remark that the “sky was the limit” as far as his flexibility would go, have all been equally welcome.

‘Most of these have been targeted killings,’ says one doctor, but he’s too afraid to put his name on record. There are plainclothes policemen in the hospital

|

|

But that’s where the conversations have largely ended. Kashmir’s own leadership has been infamously flawed and internecine. Backed by the ISI and Jamaat-e- Islami, the Hurriyat faction led by Geelani has been inflexibly obdurate demanding a plebiscite and refusing to talk to India. Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and Sajjad Lone’s fathers were both assassinated, allegedly by hardline factions, for toeing a more moderate line. Neither scion — elite by lineage and temperament — has really managed to expand their political base. Yasin Malik, the JKLF commander who declared a unilateral ceasefire, also could not keep his party from fracturing. For all the emotional voltage that the call for azadi generates then, it is difficult not to notice that 20 years into their struggle, there is no unified leadership or sustained programme of political resistance in Kashmir. This is why, perhaps, grievance in Kashmir only expresses itself as cyclical eruptions.

Despite this, the current scenario offers India a tremendous opportunity. Whatever their failings, all three leaders — the Mirwaiz, Malik and Lone — have very reasonable positions. All of them recognise that, learning from the cataclysm of the militancy, Kashmiri society is collectively transiting into a non-violent phase of resistance. “The boys who once carried AK- 47s and LMGs are now not killing but getting killed. This transition needs to be respected and preserved,” says Malik. In fact, he says he has had much to do with this subliminal psychological shift. In 2003, he launched a signature campaign across Kashmir over two years, visiting schools, colleges and migrant camps in Jammu, to awaken people to the fact that Kashmir was not merely a territorial dispute between India and Pakistan, but that Kashmiri people too had a say in it. He collected 1.5 million signatures. In 2007 again, he launched a Freedom March over 116 days, meeting over three million people. Inspired by Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi, he says, “I want to build a disciplined movement. For that you have to prepare people mentally.”

MALIK, IN fact, has no fixed position on a ‘Kashmir solution’. “I firmly believe solutions arise from the process,” he says. “We have to sit across the table and understand and accept each others’ compulsions. Most importantly, we have to seek common ground with Jammu, Azad Kashmir, Gilgit, Baltistan, Kargil and Leh. We all know that dividing this region up on communal grounds would have disastrous consequences for the subcontinent.”

|

Let us be An old man pleads with securitymen during a curfew in Srinagar

PHOTO: ZULFQAR KHAN |

|

The Mirwaiz too has been introspecting. “We have made a mistake in not institutionalising the resistance movement,” says he. “It is a very encouraging sign that right now, no one in Kashmir is looking towards Islamabad. This is our battle; it is a homogenous, indigenous movement. All of us have invested a lot in keeping this process peaceful. But we have not managed to build any social organisations that can reach out to the people who suffer when there are hartals and curfews. I am now trying to call an all-party meeting to build a more sustainable platform.”

But here too, the ball lies in India’s court. In a curiously cynical move, successive governments at the Centre have systematically diminished the moderate leaders in Kashmir and discredited the dialogue process. Each time a leader has reached out to them to talk conditions of peace, they have sent them back emptyhanded — looking effete and sold out. Or they have compromised their reputation with selective leaks and statements. Firdaus Syed, a contemplative man, better known once as Baba Badr, the commander of Muslim Janbaaz Force, recalls the time he first reached out to talk peace from across the border in 1996. He was sickened by the cycles of violence that had engulfed society. He mentions how an ikhwani (counter-insurgent) was forced by the army to rape a former comrade’s sister as a humiliation for not being able to track him down.

“The most difficult position in a conflict is the moderate position. Delhi sees us as Kashmiri and Kashmiris see us as sell outs. But even as we were talking with Home Minister SB Chavan, Krishna Rao, who was the governor then, made a statement that the boys had no option but to surrender. Dialogue immediately became surrender and we were utterly discredited,” he says. “Besides, their only goal was to turn us into counter-insurgents. We thought of ourselves as instruments of peace. We had not set out to become their clients and fight our own people.”

This story repeats itself with depressing frequency. Earlier this year, when Home Minister Chidambaram invited the Mirwaiz for “quiet talks”, he found himself similarly exposed by a journalist. Earlier, on the invitation of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, Sajjad Lone spent a year writing up a document on Achievable Nationhood, but when he finished apparently Singh never gave him time to discuss it. In doing all of this — in systematically cutting the moderates to size — the Indian government has inadvertently played a huge role in building up the seemingly unassailable aura around the more hardline Geelani. Again and again, thought leaders in Kashmir assert Delhi has to make up it mind whether it really wishes to address the problem in Kashmir. If not, it probably suits them to have Geelani around making Kashmir look an insoluble issue.

The furious stones being hurled at India’s security forces come bearing all these questions. Is India really looking to “sort this out”? Interestingly, Geelani himself looks in a mood to talk. Having pitched himself too high, and with a 110 deaths on his hands, he’s looking for a dignified climb-down. A senior police officer says, “This time Geelani’s four points look very encouraging. The fifth point about an ‘international dispute’ is merely a matter of semantics.” Geelani himself says much the same. “If India is already talking to Pakistan and other separatist Kashmiri leaders, it is already acknowledging that there is a dispute. Or else, why would it be talking? So what’s the harm in accepting my five points?”

This brings us back to the question everyone in Kashmir is asking: why is India not seizing the opportunity?

|

Shock treatment A terrified family surveys the damage after yet another round of firing

PHOTO: ABID BHATT |

|

IF YOU talk to Kashmiri journalists at Cafe Arabeca in Srinagar, you will be filled with dread. There is a sense of impending doom. If this narrow opportunity for peace is not seized, the sense is a second cycle of militancy, much more convulsive than the first, will kick in. The rumour is that the Taliban, the Maoists and the second generation Kashmiri underground are starting to form an axis.

For too long, India’s response to a crisis in Kashmir has been to send big economic packages. “Imagine you are a rich businessman and an absent father. You can keep opening your wallet for your child and he might keep taking your money, but will that substitute for parenting?” asks Firdaus. Malik agrees. “When you are governing a place, you owe it some responsibilities. The British Raj too built railways and schools and roads in India. But that could not stop India from asking for its independence through a political process.”

There is a growing sense of doom. The rumour is that the Taliban, the Maoists and the second generation Kashmiri underground are starting to form an axis

|

|

Lone puts it more bluntly. “It is true that India does not even send rice to Bihar while it sends cream to Kashmir. But this cannot substitute a political response because instead of giving it to us with dignity, it serves it to us in a slipper.”

Unfortunately, three senior Congress leaders turned down the offer to lead the political process in Kashmir. But BJP leader Arun Jaitley, who was part of the all-party delegation, says he was moved enough to change some of his stances. “I have come to believe that the issues of discrimination in Jammu and Ladakh must be addressed separately. The issues of the Valley cannot be linked to that. In the Valley, the policy should be to weaken the separatist leaders’ hold and win people’s hearts.”

Another leader, requesting anonymity, suggests that there should be a five percent reservation in India in schools and jobs for the North-east and Kashmir. We must increase their stakes in India. This will go a much longer way in national integration than any artificial assertion of it.”

In a curious twist, it is probably going to prove difficult to sustain a Kashmiri independence movement in a globalised, consumerist world. This generation of stone-throwers is also a first generation of highly educated aspirants. In Kashmir, the resentment against daily humiliations often segues into a larger idea of azadi. But if you remove these oppressions, that energy is as likely to reach for modern, contemporary ambitions. Like Rafiq, every bright Kashmiri who can is leaving for wider horizons — both in India and abroad. This might sharpen their sense of home. Or it might make the idea of porous borders and diluted nations the more attractive option.

It all depends on the answers India provides to the questions Kashmir’s stones are posing.

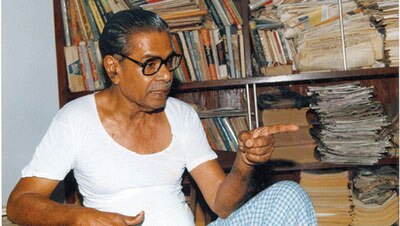

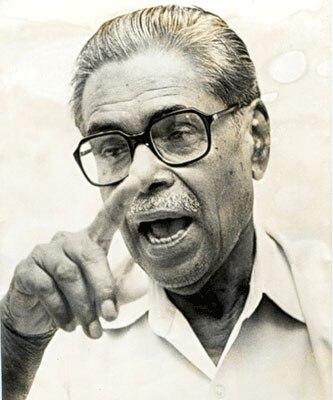

വായനയെ ആദരവോടെ സമീപിക്കുന്ന മലയാളികളില് മിക്കവര്ക്കും എം.എന്.സത്യാര്ഥി പരിചിതനാണ്; പ്രഗത്ഭനായ ഒരു വിവര്ത്തകന് എന്ന നിലയില്. ബംഗാളിയിലും ഉര്ദുവിലും ഹിന്ദിയിലുമൊക്കെയായി വ്യാപിച്ചു കിടക്കുന്ന ഇന്ത്യന് സാഹിത്യത്തിന്റെ ആത്മാവിനെ മനോഹരമായ മലയാള വിവര്ത്തനങ്ങളിലൂടെ കേരളത്തിലേക്ക് ആവാഹിച്ചു കൊണ്ടുവന്ന വ്യക്തിയാണ് സത്യാര്ഥി. കിഷന് ചന്ദിന്റെയും സാവിത്രി റോയിയുടെയും ബിമല്മിത്രയുടെയുമൊക്കെ കൃതികള് ആര്ജവത്വം ചോര്ന്നു പോകാതെ മലയാളീകരിച്ചെത്തുമ്പോള് ചിലരെങ്കിലും അത്ഭുതപ്പെടാതിരിക്കില്ല; ആരാണ് ഈ സത്യാര്ഥി, ഇത്രയും ഭാഷകളുടെ മാന്ത്രികത കരസ്ഥമാക്കിയ ഇയാള് എവിടുത്തുകാരനാണ്?

വായനയെ ആദരവോടെ സമീപിക്കുന്ന മലയാളികളില് മിക്കവര്ക്കും എം.എന്.സത്യാര്ഥി പരിചിതനാണ്; പ്രഗത്ഭനായ ഒരു വിവര്ത്തകന് എന്ന നിലയില്. ബംഗാളിയിലും ഉര്ദുവിലും ഹിന്ദിയിലുമൊക്കെയായി വ്യാപിച്ചു കിടക്കുന്ന ഇന്ത്യന് സാഹിത്യത്തിന്റെ ആത്മാവിനെ മനോഹരമായ മലയാള വിവര്ത്തനങ്ങളിലൂടെ കേരളത്തിലേക്ക് ആവാഹിച്ചു കൊണ്ടുവന്ന വ്യക്തിയാണ് സത്യാര്ഥി. കിഷന് ചന്ദിന്റെയും സാവിത്രി റോയിയുടെയും ബിമല്മിത്രയുടെയുമൊക്കെ കൃതികള് ആര്ജവത്വം ചോര്ന്നു പോകാതെ മലയാളീകരിച്ചെത്തുമ്പോള് ചിലരെങ്കിലും അത്ഭുതപ്പെടാതിരിക്കില്ല; ആരാണ് ഈ സത്യാര്ഥി, ഇത്രയും ഭാഷകളുടെ മാന്ത്രികത കരസ്ഥമാക്കിയ ഇയാള് എവിടുത്തുകാരനാണ്?

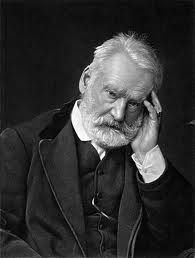

ഴാങ് വാല്ഴാങ് അര്ദ്ധരാത്രിയോടുകൂടി ഉണര്ന്നു.

ഴാങ് വാല്ഴാങ് അര്ദ്ധരാത്രിയോടുകൂടി ഉണര്ന്നു.

ശേഷം, ഴാങ് വാല്ഴാങ്ങും അവരെ മറന്നുകളഞ്ഞു, ആദ്യത്തില് ഒരു മുറിവോടുകൂടിയിരുന്ന ആ ഹൃദയത്തില് ഒരു വടുക്കെട്ടി അത്രമാത്രം. തൂലോങ്ങില് കഴിച്ചുകൂട്ടിയ അനവധി കൊല്ലങ്ങള്ക്കുള്ളില് ഒരിക്കല്മാത്രം അയാള് തന്റെ സഹോദരിയെപ്പറ്റി പറഞ്ഞുകേട്ടു. അയാള് തടവില്പ്പെട്ടതിന്റെ നാലാമത്തെ കൊല്ലമാണ് ഇതുണ്ടായതെന്നു ഞാന് വിചാരിയ്ക്കുന്നു. ഏതു വഴിക്കാണ് അയാള്ക്ക് ആ വര്ത്തമാനം കിട്ടിയതെന്ന് എനിക്കറിഞ്ഞുകൂടാ. അവരെ സ്വന്തരാജ്യത്തുവെച്ചു കണ്ടു പരിചയമുള്ള ഒരാള് ആ സഹോദരിയെ എങ്ങനെയോ കണ്ടുമുട്ടി, അവള് പാരിസ്സിലായിരുന്നു. റ്യുദ്യു ഗാന്ത്രില് സാങ്-സുല്പിസ്സ് എന്ന പള്ളിക്കടുത്തുള്ള ഒരു പൊട്ടത്തെരുവിലാണ് അവള് പാര്ത്തിരുന്നത്. എല്ലാറ്റിലുംവെച്ചു പ്രായം കുറഞ്ഞ ഒരു കുട്ടി, ഒരു ചെറിയ ആണ്കുട്ടിമാത്രം, അവളുടെ കൂടെ അന്നുണ്ടായിരുന്നു. മറ്റുള്ള ആറു കുട്ടികളും എവിടെ? ഒരു സമയം അവള്ക്കുതന്നെ നിശ്ചയമില്ലായിരിക്കും. റ്യു ദ്യു സബോവില് 8-ാം നമ്പറായ ഒരച്ചുക്കൂടത്തില് അവള് ദിവസംപ്രതി രാവിലെ പോവും; അവിടെ അവള്ക്കു കടലാസ്സു മടക്കുകയും തുന്നുകയുമായിരുന്നു പണി. രാവിലെ ആറു മണിക്കു-മഴക്കാലങ്ങളില് പുലരുന്നതിനു വളരെ മുമ്പുതന്നെ-അവള്ക്ക് അവിടെ ചെന്നുകൂടണം. ആ അച്ചുക്കൂടമുള്ള എടുപ്പില്ത്തന്നെ ഒരു ഭാഗത്ത് ഒരു സ്ക്കൂള്കൂടിയുണ്ട്; ഏഴു വയസ്സു പ്രായമുള്ള തന്റെ കുട്ടിയെ അവള് സ്കൂളിലും കൊണ്ടുപോയാക്കി. എന്നാല് അവള്ക്കു അച്ചുക്കൂടത്തില് ആറു മണിക്കു ചെല്ലേണ്ടിയിരുന്നതുകൊണ്ടും, സ്ക്കൂള് ഏഴുമണിക്കുമാത്രം തുറന്നിരുന്നതുകൊണ്ടും, സ്ക്കൂള് തുറന്നു കിട്ടുവാന്വേണ്ടി ആ കുട്ടിയ്ക്കു ഒരു മണിക്കൂര്നേരം മുറ്റത്തു നില്ക്കേണ്ടിവന്നിരുന്നു. മഴക്കാലത്തു രാത്രി മുറ്റത്തു ഒരു മണിക്കൂറോളം നില്ക്കുക! അച്ചുകൂടത്തിലേയ്ക്കു കടന്നുചെല്ലുവാന് അവിടെയുള്ളവര് ആ കുട്ടിയെ അനുവദിക്കാറില്ല; ആവശ്യമില്ലാതെ അവന് അവരെ അലട്ടിക്കൊണ്ടിരിക്കുമെന്നാണ് അവരുടെ വാദം. രാവിലെ കൂലിപ്രവൃത്തിക്കാര് പോകുമ്പോള് ആ പാവമായ ചെറുജന്തു ഉറക്കംവന്നു കുഴങ്ങി നിലത്തുള്ള കല്വിരിപ്പില് ഇരിക്കുന്നതും, പലപ്പോഴും ചൂളിപ്പിടിച്ചു തന്റെ കൊട്ടയ്ക്കുള്ളില് ചുരുണ്ടുകിടന്നുറങ്ങുന്നതും അവര് കാണും. മഴ പെയ്യുമ്പോള് പടികാവല്ക്കാരിയായ ഒരു തള്ള അവന്റെ മേല് ദയ വിചാരിക്കും. ഒരു വൈക്കോല്ക്കിടക്കയും, ഒരു നൂല്നൂല്പ് യന്ത്രവും, രണ്ടു മരക്കസാലയുമുള്ള തന്റെ ഗുഹയിലേക്ക് അവള് ആ കുട്ടിയെ കൂട്ടിക്കൊണ്ടുപോവും; അവന് അതിന്റെ ഒരു മൂലയില് തണുപ്പുകൊണ്ടുള്ള ഉപദ്രവം കുറച്ചു കുറയുവാന് വേണ്ടി പൂച്ചയെ ചേര്ത്തടുപ്പിച്ചുപിടിച്ചു ചൂളിക്കിടന്നുറങ്ങും. ഏഴു മണിക്കു സ്ക്കൂള് തുറക്കും; അവന് അകത്തേയ്ക്കു പോവും. ഇതാണ് ഴാങ് വാല്ഴാങ് കേട്ടത്.

ശേഷം, ഴാങ് വാല്ഴാങ്ങും അവരെ മറന്നുകളഞ്ഞു, ആദ്യത്തില് ഒരു മുറിവോടുകൂടിയിരുന്ന ആ ഹൃദയത്തില് ഒരു വടുക്കെട്ടി അത്രമാത്രം. തൂലോങ്ങില് കഴിച്ചുകൂട്ടിയ അനവധി കൊല്ലങ്ങള്ക്കുള്ളില് ഒരിക്കല്മാത്രം അയാള് തന്റെ സഹോദരിയെപ്പറ്റി പറഞ്ഞുകേട്ടു. അയാള് തടവില്പ്പെട്ടതിന്റെ നാലാമത്തെ കൊല്ലമാണ് ഇതുണ്ടായതെന്നു ഞാന് വിചാരിയ്ക്കുന്നു. ഏതു വഴിക്കാണ് അയാള്ക്ക് ആ വര്ത്തമാനം കിട്ടിയതെന്ന് എനിക്കറിഞ്ഞുകൂടാ. അവരെ സ്വന്തരാജ്യത്തുവെച്ചു കണ്ടു പരിചയമുള്ള ഒരാള് ആ സഹോദരിയെ എങ്ങനെയോ കണ്ടുമുട്ടി, അവള് പാരിസ്സിലായിരുന്നു. റ്യുദ്യു ഗാന്ത്രില് സാങ്-സുല്പിസ്സ് എന്ന പള്ളിക്കടുത്തുള്ള ഒരു പൊട്ടത്തെരുവിലാണ് അവള് പാര്ത്തിരുന്നത്. എല്ലാറ്റിലുംവെച്ചു പ്രായം കുറഞ്ഞ ഒരു കുട്ടി, ഒരു ചെറിയ ആണ്കുട്ടിമാത്രം, അവളുടെ കൂടെ അന്നുണ്ടായിരുന്നു. മറ്റുള്ള ആറു കുട്ടികളും എവിടെ? ഒരു സമയം അവള്ക്കുതന്നെ നിശ്ചയമില്ലായിരിക്കും. റ്യു ദ്യു സബോവില് 8-ാം നമ്പറായ ഒരച്ചുക്കൂടത്തില് അവള് ദിവസംപ്രതി രാവിലെ പോവും; അവിടെ അവള്ക്കു കടലാസ്സു മടക്കുകയും തുന്നുകയുമായിരുന്നു പണി. രാവിലെ ആറു മണിക്കു-മഴക്കാലങ്ങളില് പുലരുന്നതിനു വളരെ മുമ്പുതന്നെ-അവള്ക്ക് അവിടെ ചെന്നുകൂടണം. ആ അച്ചുക്കൂടമുള്ള എടുപ്പില്ത്തന്നെ ഒരു ഭാഗത്ത് ഒരു സ്ക്കൂള്കൂടിയുണ്ട്; ഏഴു വയസ്സു പ്രായമുള്ള തന്റെ കുട്ടിയെ അവള് സ്കൂളിലും കൊണ്ടുപോയാക്കി. എന്നാല് അവള്ക്കു അച്ചുക്കൂടത്തില് ആറു മണിക്കു ചെല്ലേണ്ടിയിരുന്നതുകൊണ്ടും, സ്ക്കൂള് ഏഴുമണിക്കുമാത്രം തുറന്നിരുന്നതുകൊണ്ടും, സ്ക്കൂള് തുറന്നു കിട്ടുവാന്വേണ്ടി ആ കുട്ടിയ്ക്കു ഒരു മണിക്കൂര്നേരം മുറ്റത്തു നില്ക്കേണ്ടിവന്നിരുന്നു. മഴക്കാലത്തു രാത്രി മുറ്റത്തു ഒരു മണിക്കൂറോളം നില്ക്കുക! അച്ചുകൂടത്തിലേയ്ക്കു കടന്നുചെല്ലുവാന് അവിടെയുള്ളവര് ആ കുട്ടിയെ അനുവദിക്കാറില്ല; ആവശ്യമില്ലാതെ അവന് അവരെ അലട്ടിക്കൊണ്ടിരിക്കുമെന്നാണ് അവരുടെ വാദം. രാവിലെ കൂലിപ്രവൃത്തിക്കാര് പോകുമ്പോള് ആ പാവമായ ചെറുജന്തു ഉറക്കംവന്നു കുഴങ്ങി നിലത്തുള്ള കല്വിരിപ്പില് ഇരിക്കുന്നതും, പലപ്പോഴും ചൂളിപ്പിടിച്ചു തന്റെ കൊട്ടയ്ക്കുള്ളില് ചുരുണ്ടുകിടന്നുറങ്ങുന്നതും അവര് കാണും. മഴ പെയ്യുമ്പോള് പടികാവല്ക്കാരിയായ ഒരു തള്ള അവന്റെ മേല് ദയ വിചാരിക്കും. ഒരു വൈക്കോല്ക്കിടക്കയും, ഒരു നൂല്നൂല്പ് യന്ത്രവും, രണ്ടു മരക്കസാലയുമുള്ള തന്റെ ഗുഹയിലേക്ക് അവള് ആ കുട്ടിയെ കൂട്ടിക്കൊണ്ടുപോവും; അവന് അതിന്റെ ഒരു മൂലയില് തണുപ്പുകൊണ്ടുള്ള ഉപദ്രവം കുറച്ചു കുറയുവാന് വേണ്ടി പൂച്ചയെ ചേര്ത്തടുപ്പിച്ചുപിടിച്ചു ചൂളിക്കിടന്നുറങ്ങും. ഏഴു മണിക്കു സ്ക്കൂള് തുറക്കും; അവന് അകത്തേയ്ക്കു പോവും. ഇതാണ് ഴാങ് വാല്ഴാങ് കേട്ടത്. പത്ത് വര്ഷം ഭരണകൂടത്തിന് ഒരു വലിയ കാലയളവല്ല. പക്ഷെ വ്യക്തിക്ക് അത് അയാളുടെ ആയുസ്സിന്റെ ആറിലൊന്നെങ്കിലുമാണ്. ഒരു നേരം ഭക്ഷണം കഴിക്കാതിരിക്കുന്നത്,കൂടി വന്നാല് ഒരു ദിവസം കഴിക്കാതിരിക്കുന്നത് പോലെയല്ല 10 വര്ഷം അത് ഉപേക്ഷിക്കുന്നത്. മണിപ്പൂരില് സായുധസേന പ്രത്യേക അധികാര നിയമ(അഎടജഅ)ത്തിനെതിരെ ഒരു ദശാബ്ദമായി ഉപവാസം നടത്തുന്ന ഈറോം ഷര്മിളയെക്കുറിച്ച് പറയുമ്പോള് മേല്പ്പറഞ്ഞ നിരിക്ഷണങ്ങള് പരിഗണനയുടെ ഏറ്റവും ഒടുവില് നില്ക്കുന്ന കാര്യങ്ങളാണ്. ഇവിടെ ചോദ്യം ചെയ്യപ്പെടുന്നത്് മനുഷ്യാവകാശത്തിന്റയും ജനാധിപത്യത്തിന്റെയും പ്രസക്തിയാണ്.

പത്ത് വര്ഷം ഭരണകൂടത്തിന് ഒരു വലിയ കാലയളവല്ല. പക്ഷെ വ്യക്തിക്ക് അത് അയാളുടെ ആയുസ്സിന്റെ ആറിലൊന്നെങ്കിലുമാണ്. ഒരു നേരം ഭക്ഷണം കഴിക്കാതിരിക്കുന്നത്,കൂടി വന്നാല് ഒരു ദിവസം കഴിക്കാതിരിക്കുന്നത് പോലെയല്ല 10 വര്ഷം അത് ഉപേക്ഷിക്കുന്നത്. മണിപ്പൂരില് സായുധസേന പ്രത്യേക അധികാര നിയമ(അഎടജഅ)ത്തിനെതിരെ ഒരു ദശാബ്ദമായി ഉപവാസം നടത്തുന്ന ഈറോം ഷര്മിളയെക്കുറിച്ച് പറയുമ്പോള് മേല്പ്പറഞ്ഞ നിരിക്ഷണങ്ങള് പരിഗണനയുടെ ഏറ്റവും ഒടുവില് നില്ക്കുന്ന കാര്യങ്ങളാണ്. ഇവിടെ ചോദ്യം ചെയ്യപ്പെടുന്നത്് മനുഷ്യാവകാശത്തിന്റയും ജനാധിപത്യത്തിന്റെയും പ്രസക്തിയാണ്.